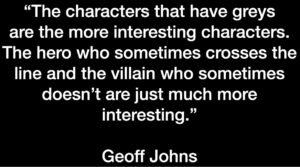

I’m engrossed in the re-writes of Blood Gift Chronicles Book 3, with characters spanning the good, the bad, and the morally grey, in this far-reaching world where ‘reap what you sow’ takes on a whole new meaning. In a recent scene with a particularly dastardly character, it got me thinking about what makes a good villain.

There’s comfort in familiar tropes, and rules: the villain must be defeated. Villains spice things up, provide licence to venture beyond usual acceptable social parameters. Since we are flawed, imperfect beings, maybe we find villains easier to relate to than heroes (though definitely not the case with my own character in question!). Perhaps there’s something similar in the way that we love horror… edge-of-your-seat fear as a form of escapism. Then there are those alternative insights: Neo’s doppleganger in The Matrix (Smith) and his comment about how we manage the world, with humans behaving in a way akin to a virus – thought provoking if not alarming.

I guess ultimately we love villains who evoke a big reaction from us: Aunt Lydia fits the bill for those we love to hate; Pennywise the Clown gives us the truly bizarre, nightmarish horror; Darth Vader’s backstory as Anakin Skywalker makes him suddenly relatable; and Circe Lanister, as despicable as she is, has those undeniable human qualities. I often think the most frightening villains, the ones who truly get under our skin, are those we can get close to, understand and imagine. It’s something that was said to Dana Scully in the X-files, when the monster she feared the most was Donnie Pfaster, because he was like the man next door. I felt the same way about the remake of The Invisible Man: this haunting tale of domestic abuse, made more terrifying with invisibility used to add god-like power to an abuser – uncomfortable, believable and easy to imagine.

But what about the morally grey? As the world moves towards a more nuanced understanding of all our complexities, so too are authors looking at the space between the binaries (me included). As promised, following my previous Breaking Binaries of Good v Bad in SFF, I’ll leave you with book recommendations for those pushing the boundaries between hero and villain.

The Second Bell by Gabriela Houston, is one of my favourite reads this year. Set in a remote mountainous community, it follows the captivating story of Salka, a girl born with two hearts, making her a striga, a dangerous demon. Among rigid laws, she must face herself, and choose: resist the innate evil inside herself, or give in. But is it really evil? Just because we’re told that something is bad, does that make it so, or should we trust our own experience?

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, looks at the impact of climate change in widening the gap between rich and poor, leading to a societal apocalypse. It’s a powerful testament to the depths humanity can sink to in the right circumstances, as well as what can thrive. The main character, Lauren, not only survives, but builds a community that she steers using her own developing philosophy she calls, Earthseed. Connecting strength to our ability to embrace change was just one message that resonated.

This is Our Undoing by Lorraine Wilson is set against a backdrop of climate change and far right politics. The MC, Lina, has many enemies, including the world of surveillance in London State, and the threats in the forests of the Rila mountains where she’s taking sanctuary. In a struggle for survival, the uneasy question is explored – who might you condemn to save another?

Weave the Lightning by Corry Lee, is set in a binaried world of resistance versus fascist state. Two main characters are on opposing sides, but faced with morally-grey choices they look beyond the confines of their worldview and search for their own truths. It’s a search that pushes boundaries and brings them closer together.

The Book of Phoenix by Nnedi Okorafor begins in NYC, where Manhattan is underwater and Tower 7 stands on Times Square. It is a place of genetic experiments on biologically altered humans, one of which is Phoenix. As Phoenix begins to question the reality of her world, she has to come to terms with her true identity and the fact that home is not home at all, but rather a prison. But when her powers are in full flight, how many will die?

The Four Profound Weaves by R.B. Lemberg is an inventive read, set in Birdverse. The MC, Uiziya is destined to become a great weaver of the four profound weaves, after which she would be able to bring the gods themselves to do her bidding. But first she must learn the fourth weave, which is the weave of death. It’s something only her Aunt Benesret can teach her, and so she waits for her aunt’s return. Benesret was banished from the community for killing people, which was necessary in learning the fourth weave. Will Uiziya be willing to do what is necessary and fulfil her destiny as a great weaver?

And lastly, a nod to the Jekyll and Hyde of internal struggles:

Claiming T-Mo by Eugen Bacon is an epic tale spanning generations. It begins with Silhouette from the planet Grovea, who is sent as a child bride to Novic, an immortal Sayneth priest of a matriarchal society. She suffers violence in the marriage, but finds joy when her son is born, who she names T-Mo. In this society, women name children, but Novic flouts the rules and names the child Odysseus. This dual naming sets in motion a Jekyll and Hyde character. And so begins a tale told through the eyes of three generations of women, who must confront their fears and navigate paths of love and acceptance.

What are you reading?